In a previous post, I talked about putting an ESP32 in my stationary bike to track my riding without relying on proprietary apps. This post picks up where that one left off: building the firmware and companion mobile app.

I used this project as my first dip into the waters of AI agent-assisted coding. Over the past year I had been hearing from more and more people who I really respect as developers that agent-assisted coding was the real deal and completely changing how they worked. It was about time I gave it a try!

If you’re more interested in the final result than my experience coding it with agentic AI, the complete project is on GitHub with a detailed feature overview. For those curious about the process, read on!

Background

Prior to this project, my main experience with AI-assisted coding was via Github Copilot (I had a free subscription for my last year as a grad student). I found it very useful as a “autocomplete on steroids”, but my experience of its limitations made me very skeptical of an LLM’s ability to be trusted with anything more than generating boilerplate or simple refactors.

What made me finally take the plunge was a friend who introduced me to agentic spec-driven development. In contrast to “vibe-coding”, where you give an AI-agent (often vague) instructions and sort of hope for the best, spec-driven focuses on first working with the agent to craft detailed specifications before implementation (defining requirements, constraints, and expected behavior), then having the agent generate code (and tests) against those specs while you verify at checkpoints along the way.

Hearing about this way of working with AI agents “clicked” for me in a way that all the hype around vibe coding never did. The “new skill” everyone was talking about wasn’t just about prompting better, it was about fundamentally changing how I think about programming: from solving problems directly to creating the right scaffolding and context for AI to solve them for me.

My stationary bike project was perfect for my first foray into agentic programming because it let me try two different working styles: With the MicroPython firmware, I was highly opinionated about the architecture and communication protocol and wanted to stay closely involved in the implementation details. With the mobile app, I focused on building user requirements and entrusted the AI with the entire Kotlin implementation, a language I had no prior experience with.

Establishing A Spec-Driven Workflow

Immediately after installing Claude Code, I gave Github’s spec-kit a spin. Spec-kit is an open-source toolkit that guides you through the spec-driven development workflow: creating specifications, generating implementation plans, breaking them into tasks, and then executing those tasks with an AI coding agent.

It quickly felt like overkill for my little project. It also was hard to tell which aspects of Claude’s behavior were a result of the spec-kit agent files vs were a part of Claude’s vanilla behavior. I decided to set the spec-kit aside for now, and get more familiarity with the base-Claude behavior before I tried other frameworks.

After some experimentation, I converged into a simplified spec-driven workflow, consisting of a root CLAUDE.md and a dev/ folder with a stages.md and a tasks.md. Each of these files I iterated on with Claude’s help over the course of the project, often asking Claude to give me options for key decisions directly in the file so I could use my code editor to easily select and edit the ideas as needed.

The root CLAUDE.md (which is read by default by Claude in every prompting context) described my project and captured my goals and design guidelines for implementation. Guidelines ranged from programming philosophy (e.g. “Simplicity first: suggest requirement changes when they enable simpler implementations”) to practical implementation parameters (e.g. “Keep Android App build / setup as simple as possible, and easy to build without Android studio”).

At the end of my CLAUDE.md I included a note pointing Claude to the /dev folder, informing it that a stages.md file existed for tracking high-level project goals and implementation stages and a tasks.md existed for tracking current actionable tasks for the active stage. You can view my CLAUDE.md on GitHub to see what the full file looked like.

Creating A High-level Development Roadmap

As I worked with Claude to write a high-level plan for my project in stages.md, Claude was able to point out some key issues that drastically changed the direction of the project as I had originally conceived of it.

When I started this project, my original plan was to run an http server on a Raspberry Pi that the ESP32 would connect to via WiFi. I figured I could have the firmware push my activity to the Pi via a simple REST API, then the Pi push my activity sessions to Google Fit via the Python API.

Unfortunately, as Claude helpfully pointed out while we co-planned the project, the Google Fit API will be deprecated in 2026. In fact as of 2024, new developers can’t even sign up to use these APIs. Instead, developers are being encouraged to migrate to Health Connect instead. (I could have also used the Fitbit Web API, but I was leery about this given Google’s slow killing of Fitbit)

Claude was very happy to brainstorm an alternative approach with me. My main concern with Health Connect was that it’s an Android API, not a REST API. So if I wanted to sync my data with Google Fit, I’d need to build a mobile app. I really didn’t want to do that at first—most of my mobile development experience has been in React Native with Expo, and diving into native Android felt like a big detour. My past encounters with native Android development involved heavy tooling (like Android Studio) that felt like overkill for a simple project like this.

But Claude reassured me we could build a lightweight setup without Android Studio by using Gradle to bootstrap a simple build environment. Given how helpful it had been already, I said “what the heck, let’s build a mobile app!”

I ended up being pretty hands-on in shaping the development plan. Claude had good instincts, but tended to focus on creating a direct path to the final result: session persistence in the firmware, then a complete Bluetooth protocol, etc. From my experience with these kinds of projects, I knew the importance of getting all the end-to-end pieces running in simple form before tackling complexity.

So I steered us toward an approach that got a simple end-to-end system up as soon as possible, and then iterated from there. My stages.md ended up containing only two stages beyond the blinking-LED proof-of-concept I had already set up (as described in my previous post): First, get BLE working in both the firmware and mobile app to create a live display of cadence. Then, extend that setup to enable session logging and a sync protocol between the bike and the app.

As I worked on implementation (next section) I found my stages.md to be a useful place to capture ideas for future features as they came up during development. Like everything else in this workflow, it wasn’t static—the file evolved as Claude and I iterated on the implementation. If you’re curious what the final version looked like, you can check out my stages.md on GitHub.

Implementation

I implemented each stage by first asking Claude to generate a new tasks.md based on my current stage. Like with the stages.md document, I had Claude walk me through a process of creating the document, giving me options and questions I could answer using my editor inside the document. When I was happy with the steps in the plan I’d tell Claude to execute specific steps or groups of steps, then to update my tasks.md accordingly. I almost always started fresh chat contexts when beginning new groups of tasks to keep Claude focused on the current work without getting distracted by earlier implementation details.

The actual development experience varied significantly between the firmware and the mobile app, reflecting my different levels of familiarity and opinions about each piece. Here’s how it played out:

Firmware

I knew before I started the project that I was going to want to have close involvement with the development of the firmware. I quickly found that it was difficult to express how I wanted problems to be solved in natural language. Because I was so familiar with Python, it was often easier to simply write something myself than explain to Claude what I wanted to see.

At this stage I used Claude much like I used GitHub Copilot: for generating boilerplate and filling in easy-to-implement items (the kind of things you’d grab from Stack Overflow).

Once I had established the basic architecture and design patterns, I found I could rely more and more on Claude executing plans from my tasks.md to extend my existing design with new features and perform sophisticated refactors. It was also an excellent rubber duck to brainstorm with (that had its own good ideas!)

That said, I found it difficult to reason with Claude about complex state and timing issues. This limitation became especially clear when working on the logic around periodic session saving: I wanted my system to periodically save sessions to memory, so that if power was lost, the current session would not be lost. But I also only wanted to record sessions that were of a minimum length, and to not count the idle time at the end of the session as part of the session. The interaction of all these requirements created some nontrivial edge cases that took considerable care to get right.

Claude would happily brainstorm what those edge cases might be, generate code to account for them, and review the code for correctness. But it often made subtle mistakes in ways that were not completely obvious. It also gravitated towards handling special cases by adding more branches rather than finding more general approaches that reduced overall complexity.

It quickly became clear this was not just a limitation on Claude’s part: my own ability to reason about correctness of these delicate situations required that I spend time implementing and iterating on the problem myself. Ultimately, I could not reliably delegate this kind of work to Claude, and needed to take full ownership of these areas of the firmware.

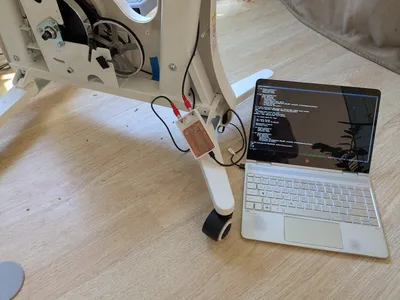

Despite these limitations with complex logic, Claude definitely felt like a boost to my productivity. The biggest wins I experienced while developing the firmware were Claude’s abilities to navigate my codebase and generate straightforward content that was otherwise tedious and time-consuming: documentation, type stubs for untyped libraries, and test harnesses that allowed me to connect to the firmware with my computer instead of the mobile app.

Mobile App

For the mobile app, I let Claude drive the entire implementation. My only input and guidance to Claude was via requirements and implementation steps in the tasks.md file. I would also use occasional interactive chat sessions to debug issues as they came up. Unlike the firmware, I didn’t care how the app was implemented, only that it met my user needs and effectively interfaced with the firmware.

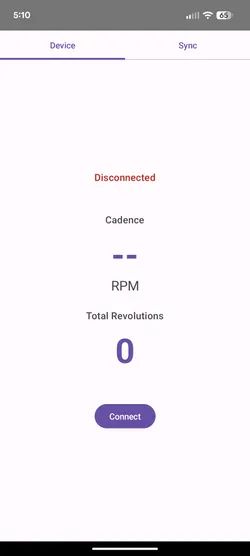

I had it start by creating a plan for the first stage of development: a simple dashboard that would update with live cadence measurements. From this high-level requirement it created a tasks.md to accomplish this including setting up a bootstrapped Gradle project, handling permission requests (so the app could scan for BLE devices), putting together a simple interface, etc.

I made some minimal modifications, and gave Claude the thumbs up to execute all the tasks. It did a bunch of work, and then guided me through the process of compiling the project and running it on my phone.

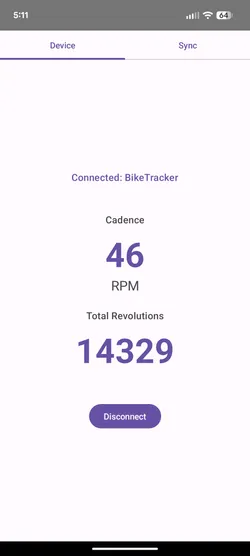

To my complete surprise, it just worked, right out of the box. I was greeted by a screen on my phone that allowed me to grant the app BLE permissions, and then got a dashboard displaying the number of revolutions and current cadence of the bike. I started pedaling, and the revolutions incremented and cadence updated.

If you’ve worked on projects like these before, then you can really appreciate what a win this was: There are often a ton of fiddly things you need to get right on the microcontroller and mobile app side in order for a system like this to work, and it’s not uncommon to spend a lot of time at the beginning of a project like this going back and forth between your system and web searches in order to get a minimal system up and running. Claude nailed it on the first try.

As I continued to iterate, not everything went perfectly the first try, of course. But I found that when Claude got stuck, I didn’t need to dive into implementation details—I could guide it at a higher level. In one notable instance, Claude struggled to get the permissions around the Google Health Connect API set up because Health Connect required a different flow than regular Android permissions. Claude got stuck in a loop trying the same things, reverting back and forth between approaches that it was convinced were correct as I tested each iteration. I told Claude to stop and do some web searches to find the proper approach. It agreed, and immediately came back with a working solution.

This became my general pattern: when Claude hit a wall, I could give it ideas of things to try or issues to investigate, and oftentimes it only required a little encouragement to get unstuck.

As I added features and iterated on the design, I continued to be impressed with how much Claude could handle at once. Having Claude generate plans I could edit in tasks.md before executing was very effective for keeping development on track. I can’t speak to the quality of code it was generating (I’m not a Kotlin dev), but for this portion of the project I only cared about the results, not the implementation details.

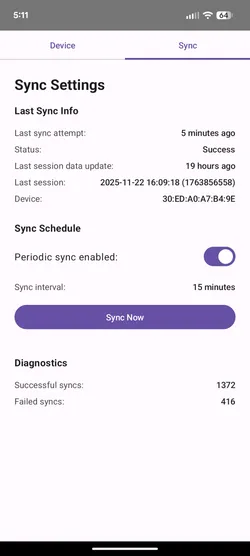

Here’s what the final app looked like:

Claude’s ability to iterate and handle complex requirements was impressive. That said, it still had the same fundamental limitation I encountered with the firmware: the ability to make guarantees about the correctness of its solutions. In this case, it wasn’t about complex logic, but other kinds of guarantees like correctly setting up a background timer to regularly wake up the phone and poll the bike for new sessions. Getting this right was non-trivial: I belatedly learned after a number of failed syncs that the phone makes decisions on whether to run these timer events based on how much battery is being used, and there are extra app permissions you can enable to give the app more control over this behavior. It took a number of attempts and a lot of interrogating Claude (and telling Claude to read the docs for me) before I knew exactly all the parts that were needed to get this to work reliably.

Takeaways and Lessons Learned

The first thing I need to acknowledge: it’s difficult to distinguish between my perception of productivity gains and the actual reality. Big successes (like Claude one-shotting the first iteration of the mobile app) were such a dopamine hit that it’s easy to forget the time spent iterating on requirements and plans to specify exactly what I wanted to build. On the surface, it felt like a modest boost in development velocity on the firmware, and a massive boost on the mobile app (I never had to learn Kotlin!). But how much of that is perception vs reality? I honestly can’t say for certain.

What I can say is that I now have a clearer understanding of the “new skill” in agentic coding that everyone has been talking about: it’s all about effectively managing the agent’s context. Until AIs have much larger context windows (and we get those cyborg brain implants), the results of agentic programming depend on your ability to communicate context and requirements, and to track what’s currently in the agent’s view.

This is where the key point of friction emerged for me: communicating what I wanted. When I didn’t know the programming language (Kotlin), communicating requirements in natural language felt natural and efficient. But for Python, a language I know intimately, breaking down my vision into natural language often felt more burdensome than just writing the code myself. These agentic workflows provided the most value when the cost of requirement communication was lower than the cost of implementation.

The interesting part is that this communication/implementation cost balance improved as the system scaled. With more established code, Claude could suggest edits that fit my paradigms and style. This is one of the reasons I think the implementation of the mobile app went so smoothly—Claude had the entire firmware codebase available as reference when planning the app.

It’s also clear to me that an experienced human always needs to be in the loop for final decisions on correctness and system guarantees. Although LLMs can create impressive results, their internal “world model” still feels unstable in unpredictable ways, especially in technical contexts where precision matters. Where experienced humans can hold logic and constraints tightly in a stable mental model, LLM reasoning seems to rely more on strong “intuition”. This works remarkably well most of the time but can subtly drift on edge cases.

Sure, you and the agent can generate tests to keep correctness in check, but for complex problems it still takes a human expert to know how well the tests cover your problem domain! As I found, this wasn’t just an AI limitation, it was a “me” limitation—I myself didn’t really understand the possible failure modes of certain parts of my system unless I was actively involved in the implementation. At the end of the day, today’s AI agents seem excellent at generating ideas and executing implementation plans, but can’t (yet) take responsibility for the final result in the same way that a human can.

Overall, I found this exercise extremely educational and I’m very happy with my resulting stationary bike system. I’m excited to work on many more projects with agents like Claude and see how the technology and our approaches to using it continue to evolve!